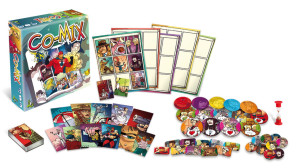

How an "Easy to Develop" Game Idea Turned Out to Be Not So Easy to Develop? Lorenzo Silva, the author of Co-Mix, posted its Design Diary on his blog on BoardGameGeek, and we are sharing it here:

"The original idea for what would eventually become Co-Mix came to me around three years ago, as one of the many small personal side-projects I start when I have an idea haunting my head, but I'm not sure whether it can be made into a proper game. The idea: "Can I create a storytelling game that makes you play cards not only to introduce plot elements, but to actually create the full story in a graphical way?"

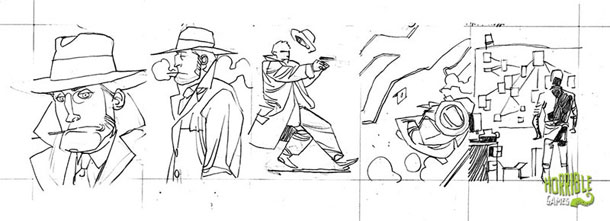

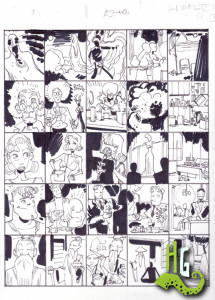

This may not seem that different from a "normal" storytelling game, but if you think about it with more attention, it's a rather unique approach, and it was never attempted before (at least to my knowledge). The ultimate goal was to give players a tool to create comics (or storyboards, if you're more familiar with cinematic terminology), to give them a game with "panel cards" depicting not only characters, objects and settings, but also "connection images" — things like shot changes, details, and actions — to fill the gaps you would usually fill with your words and storytelling skills. It doesn't sound like a difficult thing to do, right? You just have to draw those "connection images" and a bunch of the other more regular stuff and call it a day, right? Riiiiight.

But surprisingly (?), problems are always waiting for you around each corner, and I had to turn many corners before Co-Mix could eventually be born...

Problem #1: "What If the Game Developer Can't Draw?"

Answer: The development of the game abruptly faces a sudden halt. With many other projects to follow, and with my lack of drawing skills making it difficult to create a decent prototype, the "storyboard generator" project was archived as "a nice idea to investigate when there's more time for it" and put into the metaphoric drawer (and maybe also in an actual one, I'm not sure).

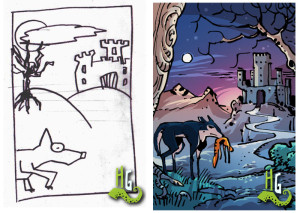

It was only after I met Matteo Cremona that new life could be brought into the project. Being a professional comic artist, Matteo could surely do a better job with those illustrations, I thought, thereby helping me to finally create a working prototype, right? Right? Well, it was right this time. Matteo turned out to be really talented, which helps a lot. Add to the mix that some time after I met him, Horrible Games was born, and you can see how the timing was perfect for the development of "The Game That Will Be Known As Co-Mix" to start again with renewed energy and enthusiasm.

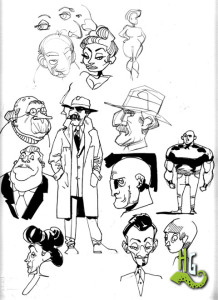

The first prototype born out of this cooperation worked surprisingly well right from the start. (It turns out that years of study and practice of drawing techniques is more helpful than an amateurish effort and a lot of good will. Who would have thought?) After six months of hard work, the game was really starting to take shape. After a lot of tweaking, we had more than three hundred illustrations, with twenty different characters recurring in many of them, sometimes even interacting with each other.

Each character also had a set of related stuff, like settings, peculiar objects, actions, and details, and all of this stuff also appeared in relation to the other characters. This gave each panel card a lot of versatility. Ideally it would be quite easy to use a panel with any other panel, even if the character it was created for was not being used in the player's story.

In addition to that, we also put into the mix a lot of "generic" panels that depicted specific actions or items or details without being associated with any other specific elements. They would work like a "joker" card; you could place them anywhere, and with the right idea, they could fit into any story.

With so many different illustrations, the decision to make the panel cards double-sided was an early and easy one. I just needed to put a lot of thought into which illustrations would be on the back of which other illustrations to avoid a situation in which a player didn't have the kind of panels he would need for his story. If, for example, we made cards with a character on the front and another one on the back, with an unlucky draft you could have found yourself in the not-so-pleasant situation of having a lot of characters in your hand, but no action to make them do, stuff to interact with, or place to be in. It would not be a pleasant game experience, trust me. But after all, it was not that big of a deal.

At this stage, as you can see above, all panel cards were still drawn in black and white. That was to save time and effort while still in the prototype stage, of course, but it leads us straight around the next corner just in time to smash our faces onto the next big problem.

Problem #2: "How to Color This Thing?"

Or even, "Do we need to color it at all?"

Some of you may need a little bit of context to make the above question not sound crazy. Traditionally, even to this day, Italian comics are mostly in black and white, just like Japanese manga and some other Asian comics. Tex Willer, Dylan Dog, Nathan Never, many of the Italian comic heroes you may have heard of — and if not, you should do some research — are published without any coloring (excluding the art on the covers and some special issues). We know and love a lot of color comics, of course, but it's not strange at all for us to read and enjoy a black-and-white comic.

And if you think about it, a black-and-white art style gives a lot of versatility to the illustration. An image of liquid pouring out of a bottle can depict anything; paint the contents of that same bottle red, and all you've got is wine, blood, or red orange juice. There's some variety, yes but you get the point.

After long and intense meditations, to give the game a broader international and age-independent appeal, I finally opted for colors. (Even in Italy, most children's comics are in color.) And that opened a whole colorful valley of possibilities! Should the colors be realistic? Dreamy? Artsy, like watercolor or something?

The style I eventually settled for was not the one I planned for during the early stages of development — although to be honest, the game started as a noir-themed game, so my initial ideas were no longer accurate anyway — but it had the right balance. It had its own identity, it suited the game well, and it may appeal to the broadest audience possible. Max Rambaldi's contribution to the coloring process was key — that, and her patience with the many slight changes, and sometimes U-turns, in art direction that she was occasionally put through.

While all of this was happening, it was quite clear that the storytelling mechanism in the game — which by this time, even though as a working title only, was already being referred to as "Co-Mix" — was working rather well. I was facing another problem though and a more difficult than expected one...

Problem #3: "How Do You Win This Game?"

The problem with any storytelling game is this: What if a player is no good at storytelling? Most of the time, the answer is that he won't be able to play in a satisfactory manner, and he won't have much fun. For most people, that's a given of the genre itself, and the one reason it's so polarizing: Some people love storytelling games, some people plainly hate them. There are not a lot of people living in the broad, desertic gray area between these two extremes. I wanted to find a way to make the game enjoyable even for people who lacked storytelling skills — that was one of the main goals — but I needed some sort of voting mechanism, so it was a bit of a Gordian knot.

When you leave judgement in the hands of players (i.e., you let players vote), you're always leaving room for people's feelings to get hurt if their efforts are systematically belittled or given a bad score — and that can happen more often than what I initially thought.

Moreover, if you happen to have at the table one of those hideous people who would give a bad score to the story that's clearly the best of the bunch just because its creator is winning — there's no hell-equivalent in any afterlife you may believe in that's harsh enough for these game-spirit-ruining fellas — and your scoring system allows those people to do that, you've got a serious problem, a problem that can totally ruin the experience of the game for a lot of people, and this is exactly what I wanted to avoid when the Co-Mix project was started.

I'm not going to summarize all the different — and differently flawed — scoring systems I tried; the months of doubts, pain, and suffering; the endless debates; the group psychotherapy and anger management session; the aborted pluri-homicidal plans and the attempted pagan and/or voodoo rites aimed at the eradication of the evil breed of good-story-downvoters from the entire globe once and for all. (I'm still tinkering with this last idea, though.) Out of frustration, I was very close to giving up and releasing the game without any voting mechanism at all, releasing it as a tool to tell stories and have fun. This was a version that playtesters, both old and new, enjoyed a lot, but even I felt that something would have been missing should I have gone through with that decision. Like the legendary Gordian knot, all that was needed was thinking a little bit outside of the box.

Suddenly, and luckily, the right idea came to me. The scoring mechanism that made the cut and went into the final game solved all of the problems I mentioned above, almost magically. It was a wonderful feeling, like seeing all the pieces of a really complicated puzzle that was going to completely ruin your life, forever and ever, finally fit together in a joyous, harmonic picture of cohesion and unity. (Okay, maybe I'm exaggerating just a tiny little bit.)

By making players say only what they liked about a story, and not how much they liked it, the problem of consistent down-voting was eliminated once and for all. It's the consensus between the players, not the players themselves, that determines the score. And by rewarding people who vote honestly — by giving bonus points to any player giving to a story the "right" vote, i.e., the one the majority of people gave — king-making was obliterated, too. With this system, it's simply not a strategy that rewards you. Yes, I'm really proud of this voting mechanism. Is it very noticeable?

And They Lived Happily Ever After?

I'm still recovering from the PTSD any bumpy game development causes a game developer, but I'll be fine eventually, thanks for asking.

Most of all, me and my crew sincerely hope that all of our efforts allow a lot of people to have half the fun we had creating and telling crazy comic stories. That's who we are — we just want to selflessly give joy to the whole world, so feel free to buy this little thing we created, and if you already did, share it with your friends and family! And convince them to buy it, too. It can be useful in many different ways! It's the Swiss Army knife of board games! Think of a rickety table, some annoying air flowing through your window, a very cold winter and an empty fireplace asking for something to burn in it..."

Follow Us on